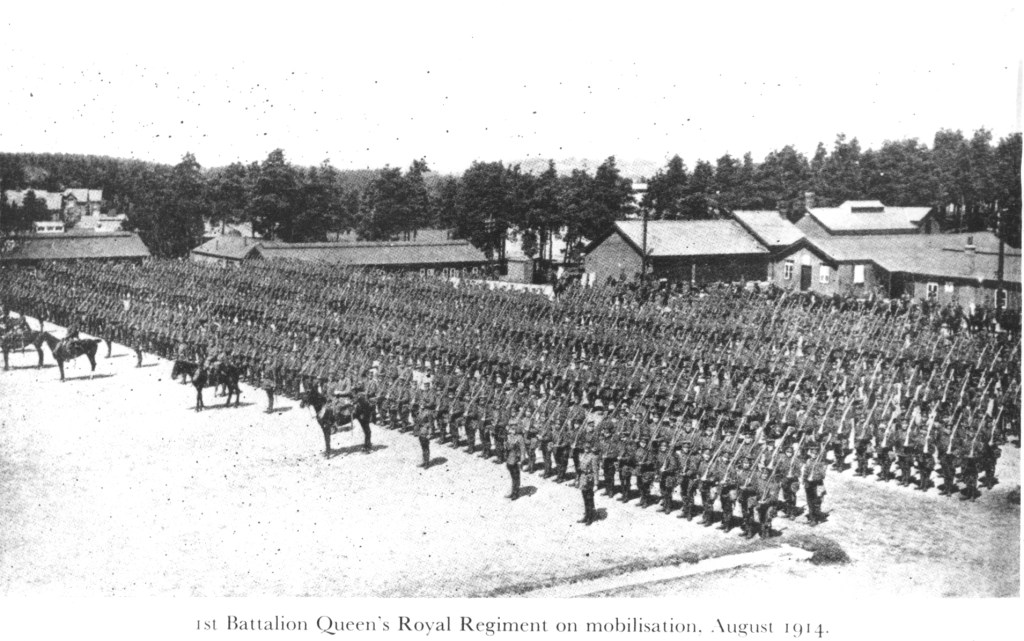

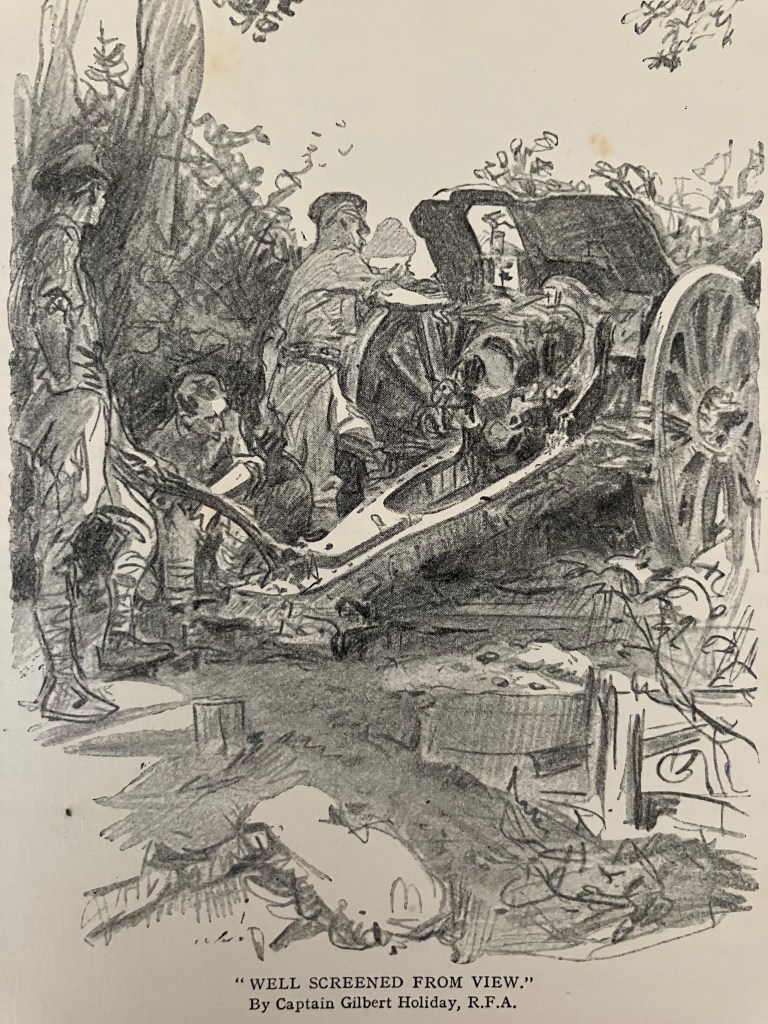

A while ago I picked up a copy of ‘The Royal Artillery War Commemoration Book’ from a charity shop. At over 400 pages and weighing in at nearly 3.5kg, this is an impressive work setting out the contribution of the Royal Artillery during the war, a not insignificant task given the scale of its involvement. The book is beautifully illustrated with many contemporary drawings and paintings, and includes a roll of honour of officers who died as well as examples of members of its ranks who received gallantry awards.

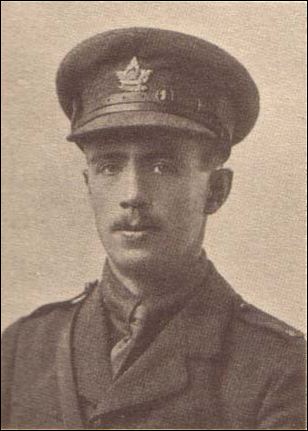

Whilst flicking through the book, I came across a letter and a postcard placed between two of the pages. The letter was signed, but I could not decipher the scrawl. However, after appealing for help on Twitter, ‘W Noel Cornelius’ was suggested. This turned out to be correct, and from the medal index cards I identified him as William Noel Cornelius, who served as a Lieutenant in the Royal Garrison Artillery and was overseas from October 1917.

His service record exists at the National Archives in the WO 339 series. This shows that he was born in Australia in 1884, lived near Birkenhead, and in civilian life was a grain importer and broker. He had attested in December 1915, possibly under the Derby scheme, and was mobilised in in January 1917, being posted to the Royal Artillery presumably because of his prior experience in the artillery cadet corps at Malvern College. He was sent to the No.3 Royal Garrison Artillery Cadet School in Bournemouth as a gunner, and in August he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant. He was presumably promoted to Lieutenant after going overseas, where he served with 280 Siege Battery until he was demobilised in 1919.

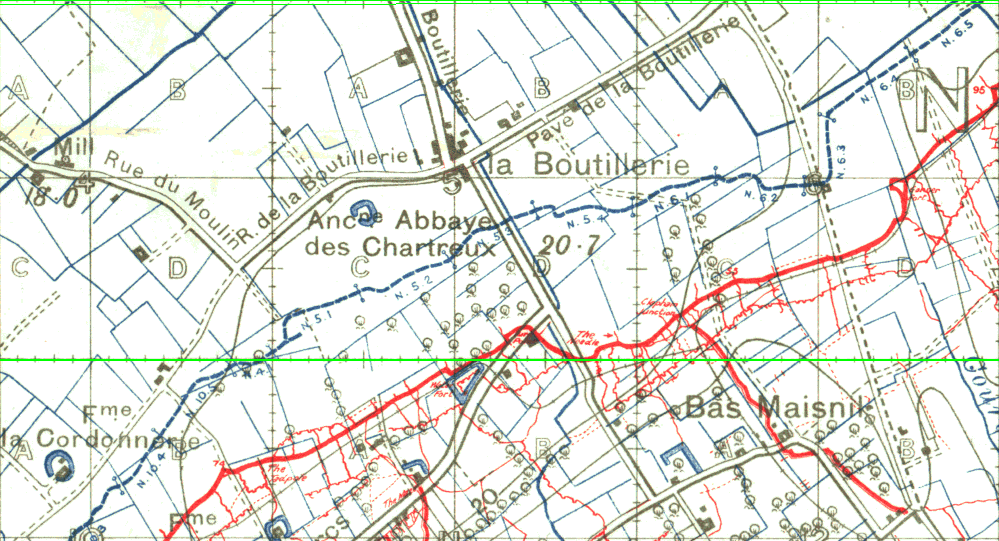

In April 1918 he was awarded the Military Cross for an action that took place south east of Ypres on 23 October 1917, just a week after he had joined his unit. The citation reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty in extinguishing a fire caused by enemy shelling. In spite of the continuance of the enemy shelling and the explosion of some of the ammunition, by this action about eighty boxes of ammunition were directly saved, and the risk to several adjacent stacks removed.”

The contents of the letter found in the book are as follows:

5 Nov 32

Dear Billie,

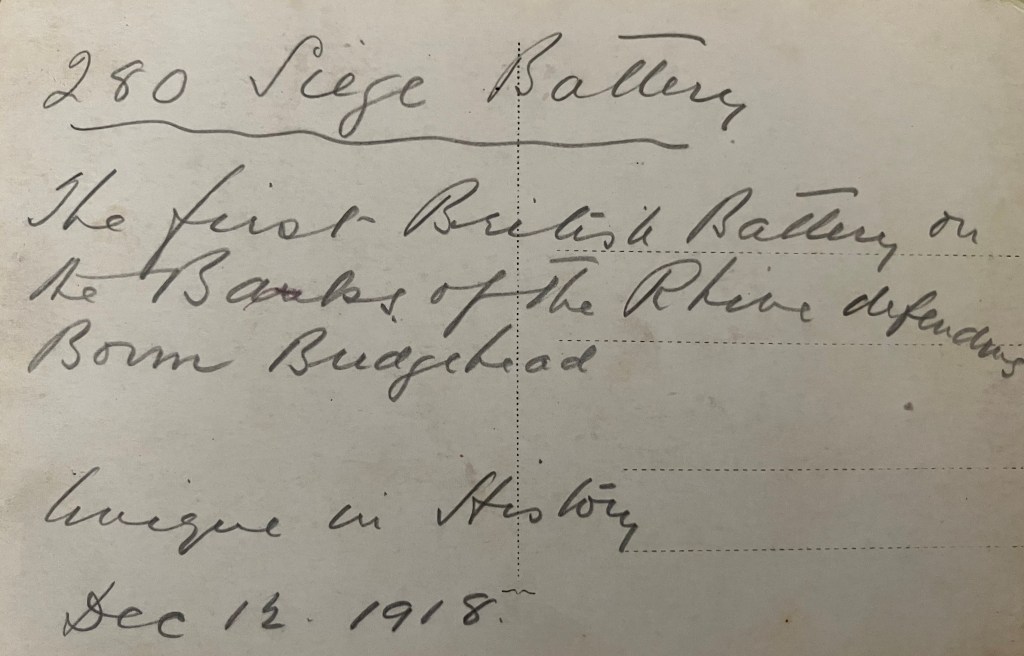

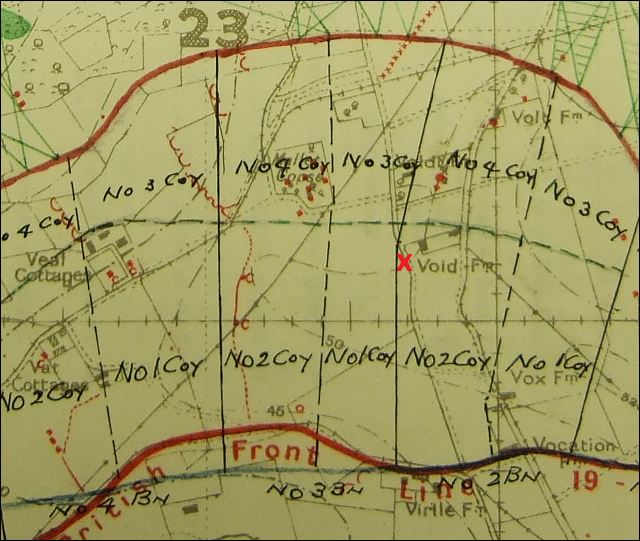

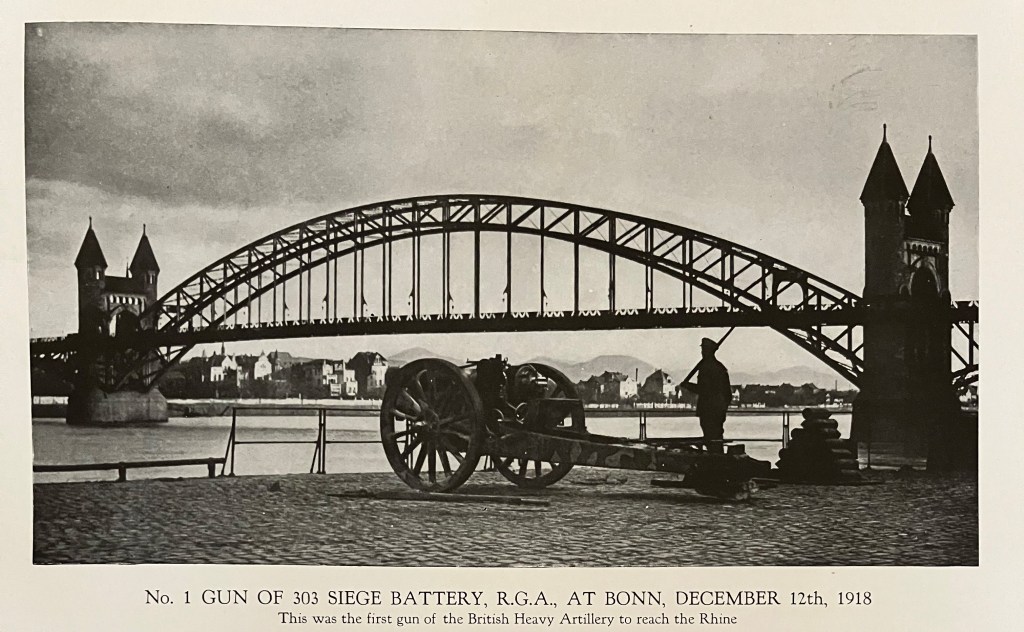

Many thanks for loan of book. I have thoroughly enjoyed it. But I have one grouse. The photo opposite page 320 of 303 Battery may be all right. But they were not the first there. Our Battery 280 SB and more particularly my right section were the 1st. I enclose a photo which I sent home at the time (see back) and I have also checked it in my diary. You will notice being the first there we had the honour of taking the right hand side of the bridge.

Yours

W Noel Cornelius

The letter relates to a photo in the book captioned “No.1 gun of 303 Siege Battery, RGA, at Bonn December 12th, 1918. This was the first gun of the British Heavy Artillery to reach the Rhine.”

The war diary for his battery does not confirm Cornelius’s assertion one way or the other, but it perhaps highlights that the official record of events may not always be correct. It seems that Cornelius was proud of his battery’s war record and felt a great wrong had been done! He died in Cheshire in 1968.